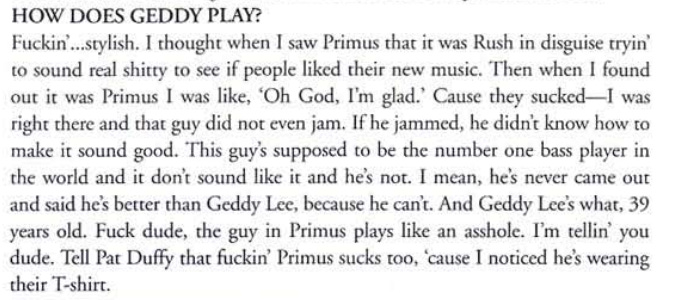

Sal Rocco Jr. From Big Brother Issue #2

Modern skateboarding has rarely existed without a soundtrack. It’s perhaps the reason contests are so boring as the juxtaposition between music and tricks are disjointed, without syncopation, and rarely created a symbiosis between skater and song. Even in the ‘70s when pool sharks slashed around to Aerosmith and Ted Nugent during backyard pool sessions the marriage of thick riffs and aggressive movement made sense. Shortly thereafter punk rock and later skate rock was born and skateboarding had its own sound. This isn’t to say that it was exclusively loud and macho as some skate rock bands ventured into surf music or funk, specifically the Big Boys from Austin, Texas who were fronted by Randy “Biscuit’ Turner, a hulking figure and pioneer gay punk performer.

As the video era was born in the ‘80s, many skate productions used generic royalty-free music or solicited tunes from friends, as well as creating often kitschy songs specifically for a project. By the ‘90s the formula was tired and hardcore punk was in a lull with the keystone acts disbanding or performing out of vouge metal-tinged punk or punk-tinged metal that was mostly terrible. Hip-hop had finally broken through to mainstream radio and underground rap artists were thriving. As skating moved from backyards to the streets, many skaters adopted hip-hop or the burgeoning indie rock scene as their soundtrack.

There was enough space between the late-’70s and ‘80s in the ‘90s for the prior decades’ music to feel retro—almost ironic much like the aesthetics associated with them. World Industries was the first brand in the early-’90s to take the skulls, neon colors, and satanic tropes of ‘80s metal and hard rock and flip them into satire. Although some skaters such as Henry Sanchez chose to use Black Sabbath’s “Symptom of the Universe” in earnest for his groundbreaking part in Tim and Henry’s Pack of Lies (1992), using music “not of the time” was often intentionally leveraged as a joke or way to get footage to stand out. The best example of the era was World Industries Love Child (1992), where the majority of the soundtrack were funk, soul, and R&B tracks from the ‘60s and ‘70s; basically considered oldies at the time and completely unfamiliar to those purchasing said video. Because skateboarding was so small, licensing rights weren’t an issue so stealing from artists as big as the Beatles went unnoticed.

As a child of the ‘70s, I grew up with AM and FM radio. AM was “light rock,” a place where you’d hear the sullen sound of the Carpenters or Gordon Lightfoot and FM, with its stronger almost alpha signal, was the home of rock music—rock spanning the studio sheen of Steely Dan to the scuzz of early pre-1984 Van Halen. Without the aid of MTV you rarely knew what a band even looked like so Foghat or Mountain seemed badass—tough biker dudes most likely with greasy hair and jailhouse tattoos. The concept is laughable in a world where the person checking out my non-GMO groceries at Whole Foods could have full face and neck ink, yet still hasn’t filled out their sleeves. Whatever, rock ‘n roll was mostly myth and even after the advent of the music video, it was more legend than tangible reality and it was impossible to think of Ozzy, Dio, Plant, Page, Madonna, Blondie, Prince, Bowie, Freddy or MJ as regular people–they were above the planet.

I quickly discovered college radio and mined the left of the dial, where I learned that there were independent and lesser-known bands that were more interesting and more relatable than what was on the big FM stations. It was hardcore punk, UK post-punk, and true metal that felt darker, heavier, sketchier and somehow more affable. Shortly thereafter I found skateboarding through BMX magazines and started to pick up on the soundtrack: Black Flag, JFA, Descendents, Dead Kennedys, Minor Threat, The Misfits, and whatever your regional starter kit was comprised of. Arena rock seemed corny. Sports seemed corny. Pro Wrestling was 100% corny. Monster truck battles on piles of dirt? Corny. Basically anything that happened in a stadium was of no interest in me and almost overnight, I was only fishing for anything below the pop culture radar.

Despite my teenage denouncement of mainstream culture, there were bands that existed in both spheres, enjoying the money and recognition of rock star celebrity while still feeling salt-of-the-Earth to fans. Iron Maiden might have been the most heralded of the ‘80s, perhaps because no matter what devilish deed their mascot Eddie was illustrated in, he was still a comic character—tongue-in-cheek or just simply a product of British humor which always seemed more sarcastic and heady than the jokesters of the US.

Post-Ozzy Sabbath was still operating making Mr. Osbourne and Ronnie James Dio’s time with the band heavy metal canon, depending on what dirt you asked. AC/DC was fine and Metallica and Slayer were still relatively underground so they stood as mid-level giants, not yet tainted by mainstream jock and future finance bros. The Beatles and Stones were ancient, Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, The Doors, and The Dead were case-by-case, often divided up by a fan’s socioeconomic background but there was one other group that managed to be agnostic of classification or genre in a sense, despite being one of the biggest hard rock acts from their country. Formed in 1968 in Toronto, Canada, Rush still stands an uncool band that’s simultaneously cool enough to avoid being corny because at their heart they were completely corny—nerds who never ceased to be nerds and never really attempted to be anything but three individuals who wanted to play articulate and precise rock music.

Rush could never be replicated because they weren’t anything but themselves. They were essentially a group of virtuosos or maybe aliens that were beamed down to a high school talent show, fully formed and just rocketing off from there. Because of this, Rush maintained and still possesses this intrinsic currency transcends a type of fan. In modern terms, the most strident Bernie Sanders or Donald Trump supporters could be absolute in their love of Rush but Rush is neither a liberal or conservative band—they’re just Rush. There really are only two camps: people who love Rush and people would love Rush if they could get over Geddy Lee’s voice.

Critics have mocked the pitch of Lee’s voice to the point of cliché, much like many have done of Billy Corgan. Even Pavement’s Stephen Malkmus once lampooned Lee’s pipes in the song “Stereo” singing:

“What about the voice of Geddy Lee

How did it get so high?

I wonder if he speaks like an ordinary guy?”

Corgan, who was born in the notoriously tough city of Chicago, Illinois, once pointed out that Ozzy’s and Lee’s careers were forged by nasally projecting over heavy music but unlike Billy Pumpkin, their public personas or in the case of Lee, almost lack of bravado made them icons not whiners.

In 1989, if you met a burly looking punker and behind the passenger seat of his rusty Ford Pinto was a shredded plastic bag full of cassette tapes, it wouldn’t be strange to find a copy of 2112 along with the Exploited, Rudimentary Peni, Samhain or whatever else you’d expect but if a copy of Cinderella’s Night Songs or God forbid, the Christian rock of Stryper, you’d start masterminding how to bail immediately. That’s because Rush—even though you were never going to have a beer with them—appeared to be regular people and Cinderella and Stryper were wearing costumes, playing music with the intention of getting big. Rush was just playing music, much like most of us were just riding skateboards. It felt like they’d be doing it in a bar if not a sold-out arena much like skating existed for many in mundane parking lots as much as it did in bustling, cool cities.

Before factory jobs and assembly lines were replaced by current-day content farms and ominous start-up roles, the major cities of the United States could fight for the proud tag of being a “working class” metropolis. There was no race for electric scooters or farm-to-table, nose-to-tail bistros. People grabbed lunch at a “roach coach” not a bespoke food truck and the world was comfortable being less cool. Sure, museums, universities and places of industry meant prosperity but the pulse of a city still beat with those who got their hands dirty making it. While it’s mostly a fallacy and olde tyme folklore but there’s something charming about a city native being so cantankerous that they champion the shitty, tedious parts of living there rather than the amenities and opportunity that cause transplants to flock there.

In 1994 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania was very much an urban landscape that espoused the concept of working class. Urban Outfitters aka Urban Gentrifiers had only recently gone public in 1993 for $18.00 a share and the Toronto Blue Jays had defeated the Phillies in the World Series that same year in six games. Philadelphia was a mix of Boston-Bitter and Jersey arrogant—irrationally confident and jaded as fuck. There were more ethnic neighborhoods than Scandanavian-inspired condominiums and it proudly wore it’s underdog warts and scars as a show of character, not inadequacy.

1994 as it was a pivotal year in Philadelphia skateboarding history and the beginning of a trend-shift in skateboarding. The deviation from tiny wheels and slowed down skating—at least on the East Coast—may have begun prior to the release of In but Dan Wolfe’s video was the most authentic depiction of a grassroots, post-LA street skating. It wasn’t that the Philly scene or East Coast were invisible prior to Real Life but the video and its reception acted as a fulcrum for an era.

411VM offered several East Coast check-ins including the stylized yet raw, Zoo York “Industry Section”(1993) and in Issue 3 (1993) specifically offered a truncated “Philadelphia Metrospective” later revisited due to footage being stolen due to camera theft but Real Life was Philadelphia’s first major skateboarding “moment.” It was selling their scene in motion that animated and endeared Philly to skateboarding. The parts live on YouTube and it’s easier to do the visual research yourself, rather than have me highlight why the Sub Zero crew stood out from the bright Southern California tech-boom of skating in the early-’90s. The footage is the statement and the results are quantifiable.

While the video doesn’t have the definitive Ricky Oyola part—that would come two years later in Dan Wolfe’s Eastern Exposure 3: Underachievers—Real Life was a 360 look at Philadelphia as a lifestyle and landscape. The video’s first full-part is Sergei Trudnowski, who begins with a symmetrical line at full-speed—kickflip, nollie flip, blast over a bump-to-bar—as Rush’s “Limelight” accents each push with a staccato rhythm. Skating down the street wasn’t a new concept as Natas Kaupas, Ray Barbee, Matt Hensley, and others had done this in prior videos in the ‘80s but Trudowski’s line stood out because it felt as if he was pushing down his street in his city—a crusty urban block, not a palm tree paved wonderland. Like his teammates Ricky Oyola and Matt Reason, the trio prided themselves on their footage mimicking their day-today—mimicking real life.

“I liked Rush when “Limelight,” it first came out,” Trudnowski says. “But when I started skating in ‘85, all the dudes with long hair that listened to Rush called me a skater fag, so we always fought the long hairs or I called them “dry heads” because their hair was mad dry! On to the Sub Zero video, I wouldn’t listen to any music those fools [The Dry Heads] liked. I heard that song [Limelight] a month before we edited that video. It just stuck with me and had known no one used a Rush song in a video. I also always thought they were sick because there were only three dudes in that band.”

In 1994 videos—especially East Coast shop videos—rarely had actual premiers but Real Life was different, with Sub Zero becoming internationally known and the city being emphatically behind the work. “Limelight’s” lyrics are a coming-out and almost meta acknowledgment of being proud of the accomplishment while downplaying it being a performance and almost game with the greatest nod being the line “living in a fisheye lens,” as Trudnowski pushes along with a bowed-out ring framing his footage. Trudnowski’s part is bookended by shots of him with his daughter Sienna and later with him in full Bertucci’s Pizzeria garb, mid-shift making deliveries as many Philly skaters did at the time. It’s more than Wolfe humanizing a pro but rather a taste of Philadelphia fuckery in that no one’s safe from a friendly jab.

Trudnowski would go on with Oyola and Matt Reason to form the core of the short-lived Zoo York subsidiary Illuminati before trademark issues lead to its dissolution. The trio moved operations to East Coast Urethane (ECU), headed by Mike Agnew under the name Silverstar. Agnew’s alleged gambling problems lead to Silverstar ending despite the demand for the brand. Trudnowski contributed another full-part during his career for Sheep Shoes’ only full-length, Life of Leisure (1997), boasting the first wallie 50-50 on a handrail and an ollie over a handrail to hill bomb on a now-infamous San Francisco street.

Ten years later, Trudnowski’s former teammate, Ricky Oyola came full-circle, contributing a full-part for Josh Stewart’s second Static video series installment, The Invisibles. By 2004, Oyola’s work ethic and nature as a mouthpiece had made him the patriarch of modern East Coast skateboarding. Though that sounds glamorous or even rock star level, the reality is that Oyola was still very much grinding out his career with family responsibilities and the weight of his independent brand, Traffic while powering through back injuries which is the most working-class shit of all time.

With pride as his biggest barrier, Oyola reluctantly took Stewart up on the opportunity to film a part for Static II, contingent on the inclusion of his new Philly clique including Jack Sabback, Rich Adler, and “New Team Rider” from the Sub Zero days, Damian Smith.

For his return to a True East® production, Oyola bangs out his brand of creative aggression to Geddy Lee and company’s pounding track, “Working Man.” Though Oyola had hammered out another great part in New Deal’s 7 Year Glitch two years prior, his Static II part had viewers dodging, weaving, and jabbing along to the section, much like the final fight in Rocky II before assuming his natural stance to blast once last Oyolan ollie to close things out as Neil Peart rattles away and Alex Lifeson’s power chord lingers and fades.

In thinking back to Trudnowski’s quote there’s a subtle synergy between Rush and the power trio of himself, Oyola, and the late Matt Reason. With the help of Roger Browne, the three skaters put Philly on the map by will alone, perfecting their craft sans piss pedaling, Hollywood Shuffles, and directing the flow of traffic at Love Park. This isn’t meant to sully the skill and contributions of DGK, the deep list of locals, a young, tech-forward Freddy Gall, and later generations, just a tribute and example of wanting to not only foster a scene but project their work ethic and discipline as far as it could beam. Though Reason never skated to Rush, he did appear in Real Life with Tool’s Cold and Ugly behind his stance-bending footage. As many would note, Tool was always seen as Rush’s descendants and with the passing of Neil Peart, the de facto torchbearers for 20-sided dice rock.

Whatever your connection to Rush, lavish drum kits, wallies or 60mm wheels is, the loss of Neil Peart and Matt Reason are reminders that influence is eternal even for those unaware of it. We can’t freeze time but history is there for anyone who wants to explore it.